Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

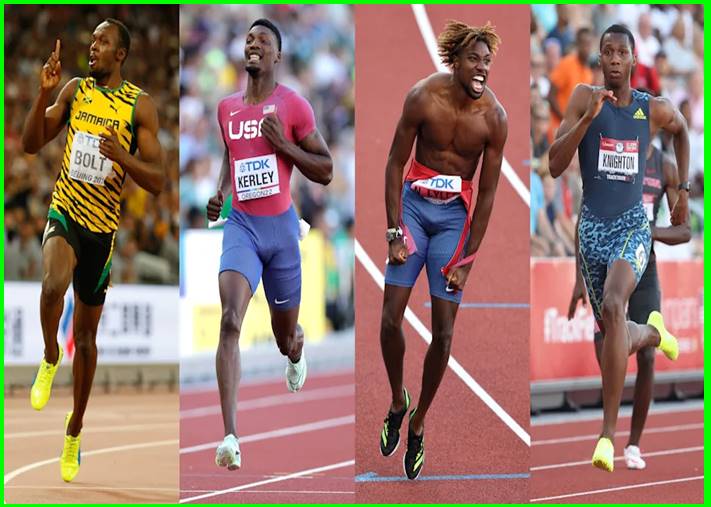

According to Quora, Usain Bolt is the fastest man in the world. In 2009, Bolt set a world record in the 100-meter sprint at 9.58 seconds, with a top speed of 27 mph. He also holds the world record for the 200-meter dash at 19.19 seconds.

Bolt was born on August 21, 1986, in Sherwood Content, Jamaica, and was previously a cricket player.

Usain Bolt

Usain Bolt. The Jamaican sprinter is the fastest human alive, our reality’s version of the Flash. He set a world record in 2009 in the 100-meter sprint at 9.58 seconds. His top speed was 27 mph.

Usain Bolt holds the title of the fastest human ever recorded. He set the world record for the 100 meters with a time of 9.58 seconds, and for the 200 meters with a time of 19.19 seconds, both achieved at the 2009 World Championships in Berlin, Germany.

These records still stand as of my last update.

It’s important to note that records may change, and new athletes may emerge with faster times. To get the most up-to-date information on the fastest human beings, you should check the latest sources for current records and achievements in track and field.

The fastest ever recorded is Usain Bolt. But the fastest we know about was an Aboriginal teenager, probably a boy, who lived tens of thousands of years ago and left their preserved footprints in the soil of Australia, going as fast as Bolt and still accelerating. We need to find out whether they were trying to catch lunch, avoid becoming something else’s lunch, or just run for the thrill of it or to impress a girl.

Usain Bolt.

The Jamaican sprinter is the fastest human alive, our reality’s version of the Flash. He set a world record in 2009 in the 100-meter sprint at 9.58 seconds. His top speed was 27 mph. However, Australian Aboriginals may have been even faster as footprints fossilized in a claypan lake bed showed that a Prehistoric Man reached speeds of up to 23 mph (37 kph) while chasing prey on a soft, muddy lake edge.

If Ancient man were warped to today’s time and had all the advantages that Bolt has in terms of proper footwear, like spiked shoes, adequate training, and rubberized tracks, then they would have reached speeds of up to 45 kph, running even faster than the fastest man alive.

BONUS FACT: A Neanderthal woman would be more potent than Arnold, the “Terminator” today, according to a leading anthropologist. The men and women of yesterday were vastly more powerful than the men and women of today.

Scientists say if there was some way to push off faster huma, ns should be able, based on their gait, to run at speeds of 30 to 40 mph briefly. The fastest known speed ever recorded was Aboriginal, and Australia was going as fast as a bolt and still accelerating.

Both are the fastest-known men, which is very subjective because if you go to some of these underdeveloped countries, you might find faster other peoplefaster people. They don’t have the opportunity. A laser measured his speed briefly at 27 and a half miles an hour.

How fast can a human theoretically run?

Humans are not the fastest animals. It is immediately apparent from our anatomy. We have heavy calf muscles way down our legs. The calves must swing back and forth at every leg stroke and require a lot of force to allow any increase of the frequency of the steps. Considering that our muscles have few “fast trigger” fibres, a frequency of about five steps per second (300 steps per minute) is an upper limit for the capacity of our leg muscles to contract and extend.

Cheetahs, ostriches, horses, and even dogs and cats have all the leg muscles bundled way up their legs and connected to their lower points of action by long tendons. This way, free of muscles, the lower part of their legs is very light and can swing at a much higher frequency. Their short muscles being closer to the point of rotation (the hip), don’t have to move so much as our long leg muscles, and the force needed to swing a largely muscle-free, very light leg is a lot less than the force required to swing the heavy, muscular human leg.

We also have a relatively short foot. The foot is an extra leverage that allows us to use the power of the calf muscles (when we walk, as opposed to running, the calf muscles are used very little). The foot acts like a gear: the shorter, the lighter the gear, the greater the force, but the lower the speed. The human foot allows the calf muscle to exert much force on the toes but not much speed. Like a taller gear, a longer foot will provide less force but more incredible speed.

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

If you look at runner animals (cheetahs, ostriches, horses, dogs, cats, etc.), they all walk on their toes, and their feet are very long, sometimes as long as the other leg bones. Humans are like motor vehicles with gearboxes stuck in second gear, while runner animals benefit from tall gear for fast running.

So, if we can swing our legs at a frequency of about five steps per second, and each step can be 2.5 m long, this means that the top speed of a human cannot exceed 12.5 m per second, which is equal to 45 km/h or 28 MPH, no matter how strong our legs are. These numbers apply to Usain Bolt; for an average human, the maximum speed is more like 30 km/h or 18 MPH. That’s fast but less than fast-running animals. A fit human cannot outrun a bear, horse, or large dog. But… we can outrun all of them on the long distance.

It is often believed that humans are weak animals that manage to get through the hardship of fighting for survival with their large brains. It is not the whole story. It is not much appreciated that humans, given certain conditions, can outrun ANY land-going animal on a long distance. Yes, I wrote ANY, including ostriches, horses and even camels.

How is that? For three extraordinary evolutionary traits of humans: we have evolved the most efficient engine water cooling system in the animal world, we are the only animal with a two-gear shifter, and we are among the few land animals to have rear wheels, sorry, hind legs, drive. Let’s see how.

Water cooling

Muscles, like all engines, produce heat. The chemical energy they receive from the blood cannot be entirely converted into mechanical energy, only a fraction of it. The rest becomes heat. Heat is good for us: we are homeothermal (hot-blooded) animals, and our body temperature must be within a very narrow range to allow us to live and thrive. Too much heat, if not adequately dissipated, will raise the body temperature and risk our survival.

The muscles of a mammal have an efficiency of about 18 to 26%. It means that 18 to 26% of the energy from the blood is converted into mechanical energy, and the remaining 74 to 82% is either not drawn from the blood or is converted into heat. If you think of it, that’s a lot of heat, and it isn’t easy to dissipate adequately.

Heat is dissipated through the skin mainly, and the surface of the skin is just so much. As a body grows more prominent, its volume increases with the cubic power of its linear dimensions (length, height), but its outer surface rises only with the square power.

If you double the size of an animal, all the rest remaining equal, its body volume will increase eight times, and its skin will surface four times. So, a big animal will soon have a deficit of body surface through which it can dissipate the heat its muscles produce.

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

The evolutionary solutions to this problem are multiple: elephants have developed large ears with a thick network of blood vessels that act as radiators to dissipate heat; other animals placed a limit to the amount of heat they produce by reducing muscle metabolism when they need to make long-duration efforts. Others have started sweating.

How does sweating help dissipate heat? Water requires a lot of heat to evaporate: almost 2300 Joule (550 calories) per gram of liquid water that becomes vapour. Water does not have to be taken to its boiling point to evaporate: it can disappear at any temperature if energy is given to it in different ways, for example, by a current of air that flows by its surface.

Now imagine having your skin constantly wet, and the current of air generated by running makes this layer of water evaporate. Continuous sweating replaces the water that evaporates. Every gram of evaporated water will remove 2300 Joules of heat from your skin. Your skin blood vessels will transfer heat from the blood to the skin and from there to the water.

An athlete can produce as many as 3 litres of sweat per hour; this corresponds to 3000 grams, and if they all evaporate, they will require nearly seven million Joules of energy. If this is done in one hour, it equals almost two kilowatts of cooling power.

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

So, we humans have a cooling system that can reach nearly two kilowatts of thermal power. It removes much of the heat our muscles produce and allows us to keep our body temperature stable even under a continuous and intense muscular effort. Assuming a cooling efficiency of 100% (never reached), we could generate a constant muscular power of 0.6 to 0.9 horsepower.

This is why we have no fur: fur insulates the layer of sweat that lies on the skin, preventing the air current from making it evaporate. Horses also sweat, but their fur, however short, requires that a much thicker layer of water is formed on their skin than on the bare skin of a human.

Heat transmission is far worse across a thick layer of liquid water trapped in the fur, as anyone sweating through a flannel shirt has experienced.

Humans have the most efficient water cooling system in the animal world. This feature did not evolve without pain. We had to lose all our body hair, except on top of the head, where it was necessary to protect the brain from heating by direct sunlight.

We had to develop a complicated and fragile kidney system that allowed us to get rid of a lot of water through a different path. We had to create a pigment to protect our skin from sun rays, and despite that, we are too often victims of skin cancer. We have become dependent on water as sweating is so hardwired in our physiology that we sweat when water cannot evaporate from our skin. But there is more.

2. two gears shifter

Unique among all animals (I’d like to be corrected here by a zoologist who knows better), humans can switch from plantigrade deambulation to digitigrade deambulation at will. When we walk, we place the entire foot on the ground, and we exploit the leverage offered by the foot’s length to lift the leg’s weight a short distance.

We almost do not use our calf muscles to walk. Why? Because less muscle mass is used, less energy is consumed, and less heat is produced. Walking is a slow but highly energy-efficient way to move. Cats, dogs, horses, camels, ostriches, cheetahs, and all other running animals always carry on their toe tips, no matter how slow they want to go.

They cannot put their calf muscles at rest, and their slow walking pace is not as efficient as if they could walk on their soles as humans (and bears) do.

When we want to run, however, we shift to a higher gear: we do not put the whole sole of our feet on the ground any more, and we run on our toes (actually, we primarily use the “cushions of the feet” behind the toes, with the toes acting as balancers).

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

This way, the calf muscles can generate a strong force acting on the leverage provided by the length of the foot to lift the body’s entire weight, and we can efficiently use many more muscles when running than when walking.

So, we have two gears: a light one for energy-efficient, slow walking and a tall one for strong, fast running or climbing. Also, this feature did not develop without losing some previous ability: for example, we lost the rear “han, ds”, which our ancestors probably shared with arboreal apes.

Although our species adapted to running, it never became a fast runner because a long foot, necessary to allow fast running, would have become somewhat awkward and useless when walking in” first gear”. But there is more.

3. hind legs drive

Once again, unique among mammals, we walk solely on our hind legs. We share this ability only with running birds. Most “two-legged” mammals are four-legged and occasionally walk on their hind legs: bears, apes, monkeys, and lemurs, for example. Australians here will dispute that kangaroos and wallabies also are bipedal.

But the fact is that they don’t walk at all. Instead, their evolution led to an even more radical transformation, and they became two-legged pogo sticks, where the two legs can only move at the same time as if they were one. Kangaroos and wallabies are, by all means, one-legged deambulatory, at least from a functional point of view.

Becoming two-legged, erect walkers was probably humans’ most painful evolution. The backbone, designed to work as a beam supported by the chest, its tendons and muscles, had to transform into a column, with many associated changes and problems. The pelvis had to become narrower to allow for a different position of the hips.

It and the oversized cranium of human fetuses have made giving birth a rather complicated affair. The cardiovascular system had to adapt and transform to account for a difference in static pressure between the head and the feet equal or greater than the systolic pressure generated by the heart and to allow the blood to flow back from the feet to the heart, overcoming a static pressure differential of 80-90 mmHg without blowing the veins of the legs (this pressure difference causes varicose veins).

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

But walking and running on two legs instead of four allowed us to use fewer muscles and fewer joints, increase our efficiency and save energy (not to mention the advantage of having one’s head and sensory organs above the tallest bushes)—one further adaptation towards long-distance mobility.

So, our species developed from a primate ancestor, which resembled a lot more modern apes than it could resemble modern humans. We lost our body fur, we developed a robust system to keep our skin wet and dissipate heat generated by the muscles so that we could endure continuous sustained efforts, we developed legs that allowed us to walk efficiently and run reasonably fast, we changed the position of our spine from nearly horizontal to vertical, and we lost a lot of physical abilities in the process.

We became the ultra-marathon runners of the animal kingdom. No other animal can run for 8 hours at 16 km/h (10 MPH) [What’s an Ultramarathon?] in a hot climate. A horse can run much faster than a man, but after one hour, even less in a hot environment, they have to stop and cool off, or they will die of a heart stroke.

In a cold climate, the problem of body heating could be more relevant: sledge dogs can run for 200 km at sub-zero temperatures, and horses travel longer and faster in the cold. But humans are unbeatable for their endurance in a hot climate.

Arabic camels are often cited as the endurance runners of the animal kingdom.

Arabic camels have a wholly different strategy from men to endure efforts, and like horses, they can only sustain solid efforts for a short time. Camels are designed to spare water. Because of their evolved environment, they cannot afford to sweat like we do, and their body temperature would rapidly increase if they did not reduce their effort.

A camel can travel for 8–10 hours but at the speed of a fast-walking human. Also, humans can do that; most people in a caravan of camels crossing a desert walk alongside the camels, but humans can also do better. They can run the same distance in less time than a camel.

During the “great Australian camel races held in 1988, the winning walked and ran alongside his camel for 3200 km (2000 miles) from Ayers Rock to Gold Coast. Man and camel had the same long-distance performance!

Why did we evolve this way? For some yet disputed reason, we became nomadic. We had to change the environment quickly to find food and shelter. The proof of this is that humans exited East Africa, where they originated and adapted to the diverse environments of Asia and Europe very early in this species, while most other primates are still there, clinging to their shrinking ecosystems.

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

All this was thanks to sweating, legs that allot efficiently to walking and running, and bipedal deambulation. Incidentally, this last feature left our hands free, allowing our brains to grow. After this, we all know how it went.

Today, we are primarily a domesticated species that has lost most of its ability to walk and run. We have almost forgotten that once upon a time, we were wild animals roaming the African savannah and beyond, walking so far that no pack of wolves or lions could follow us.

We could disappear from their hunting grounds and be beyond the horizon overnight. Cool!

EDIT #1: thanks to Cole, who noted that humans can run as fast as 28MPH. That’s just one human. How fast does Usain Bolt run in mph/km per hour? Is he the fastest-recorded human? 100m record? And 20MPH is a more realistic figure for “normal” humans. I have, however, changed my numbers accordingly.

Edit #2: Thank you for the many upvotes, but mainly for the exciting discussion that is going on in the comments section, which I invite the readers of this answer to scroll.

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run?

It is time for me to confess: I write this kind of answer mainly for the pleasure of the discussion rather than for the upvotes.

I have no definitive proof that man is the best long-distance runner in the animal world, and my statement in this sense is provocative. I wanted to be challenged in this (and other statements), and indeed, the challenges came, and I collected some fascinating information in the comments.

Fascinating is the real-life account by Pat McCormack and the long comment by Ian Dorward. Also, thanks to Tim Lu, who disputed my numbers on the cooling power of sweating and prompted me to do some calculations on an Excel sheet, of which you can read the results in my answer to his comment.

I also want to thank all those who kindly took the time to proofread my answer, found several grammatical errors and suggested edits. English is not my native language, so correcting my writing is for me to learn something new.

EDIT #3: I found out that Quora do not recognize the edits and corrections that many readers are kindly suggesting, and I keep seeing the same typos over and over despite accepting the corrections. I went through the text, corrected them manually, and took the chance to make minor changes and additions. Among them is a mention of the Great Australian Camel Race that was held in 1988.

How Fast Is the World’s Fastest Human?

In 2009, Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt set the world record in the 100-meter sprint at 9.58 seconds. For those of us more accustomed to sitting than sprinting, to translate this feat into terms of speed is to underscore the stunning nature of Bolt’s performance.

Speed is the rate at which an object (or person) moves through time. It is mathematically represented as speed = d/t (where d is distance and t is time). That means Bolt’s speed during his world-record run was 10.44 meters per second. Since many people are more familiar with automobiles and speed limits, it might be more helpful to think of this in terms of kilometres per hour or miles per hour: 37.58 or 23.35, respectively.

That’s faster than the estimated average traffic speed for the U.S. cities of Boston, New York City, and San Francisco. Even more astounding is that Bolt started from zero speed and then had to accelerate, which means that his top speed was faster.

In 2011, Belgian scientists used lasers to measure Bolt’s performance in the stages of a 100-meter race held in September.

They found that 67.13 meters into the race, Bolt reached a top speed of 43.99 kilometres per hour (27.33 miles per hour). He finished with a time of 9.76 seconds in that race, but research has suggested that, with his body type, he probably shouldn’t even be competitive at that distance. From a biomechanical perspective, the fastest sprinters are relatively short, and their muscles are loaded with fast-twitch fibres for rapid acceleration.

The elite sprinter is a compact athlete, not a tall and lean one. Given his size—head and shoulders above the other competitors—Bolt should be last off the blocks and across the finish line. And yet he is the fastest man in the world.

Could Usain Bolt be the fastest human ever to live?

Using the extrapolation method, Usain Bolt may not be the fastest human being ever to live. Biologically, Bolt is a descendant of people of African origin who migrated to the Americas only a few hundred years ago through the slave trade. If DNA was done on him, we could get a perfect match in Africa. Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run

If we consider his biological makeup, there should be dozens of people like him. The biggest problem in finding people with similar physical characteristics who can challenge him on the track is that. It’s not funny, but most people from some impoverished areas of Africa never/will never get a chance to discover their athletic talent.

The main reason is that those selected are extremely lucky to have been chosen because someone saw them competing at a school level. Education is still not readily accessible in some parts of Africa.

So the bottom line is that we will never know if he is the fastest person ever, but for now, because he was privileged enough to do what he is doing, he is by all means the most immediate.

Contrary to popular opinion, it’s not Usain Bolt. Footprints found in a dried-up lake bed in Australia indicated a young man running faster than our Mr Bolt. They can’t tell if the youth was running to catch something or fleeing in panic to escape being caught by something.

I’ll get a reference to back this up.

Humans can run faster if they can use brush spikes to gain more excellent traction. After introducing those spikes, there was a slew of speed records, but they were erased, and the spikes were banned from the Mexico Olympics in 1968.

There is also the issue of whether a person under the influence of enhancing agents, as Ben Johnson did in 1992, should be considered. What we have are approved records recognised by athletic bodies.

How fast and for how long can humans run?

Usain Bolt set the top speed for men during the 100-meter sprint during the World Championships in Berlin on August 16, 2009. He finished with a record time of 9.58 seconds and has been called the best human sprinter. Florence Griffith-Joyner has held the record for the fastest woman for over 30 years.

On July 16, 1988, she ran the 100-meter dash in 10.49 seconds at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Dean Karnazes made headlines in 2016 for running 350 miles in 80 hours and 44 minutes without stopping for sleep. Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run

How far can a trained human run full speed without stopping?

Full speed is relative.

A Greek man named Yiannis Kouros did slightly over 188 miles in 24 hours a few years ago. That wasn’t a dead sprint, but you can bet he wasn’t going slow.

There is nothing on land that can outrun a human over long distances.

How fast can the fastest person in the world run?

Usain Bolt ran the 60–70m portion of the 100m final at the 2009 IAAF World Championships in Berlin — the very race where he set the current world record of 9.58 — in 0.81 seconds, for a top speed of 12.35 m/s, or 44.4 km/h.

His entire 10m splits, here compared to Beijing 2008 when he famously broke the world record with his shoelaces untied, slowing down and pumping his chest near the finish line:

Usain Bolt 10 meter splits, Fastest Top Speed, 2008 vs 2009

(Notice how he was quicker to 10m in Beijing than in Berlin, even though his reaction time was worse.)

It is the fastest anyone has ever run under valid race conditions. If you relax the ‘valid race condition’ constraint, Tyson Gay ran a faster wind-aided (+4.1 m/s) split in the 2008 trials: both his 50–60m and 60–70m splits were recorded in a staggering 0.8 sec each, for a top speed of 12.5 m/s or 45 km/h.Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run

I mean, look at these numbers:

Unfortunately for Tyson, his next race was the 200-meter heats, where he severely injured his hamstring. I still don’t think he would’ve beat Usain because it’s the second half of the race where Usain’s ability to maintain his top-end speed shines (it’s clear when you look at the splits in the first table), but by Jove, it would’ve been a hell of a finish.

Tangentially, Usain did all this despite his right leg being half an inch shorter than his left due to scoliosis curving his spine to the right. This results in an uneven stride, which usually spells death for sprinters hoping to run on the world stage.

It’s pretty significant: his right leg strikes the track with about 1,080 pounds of peak force (as measured in the middle 30 milliseconds of the impact delivered, what SMU physicist Laurence Ryan calls “30 ms to glory”); his left leg provides ‘only’ 955 pounds in comparison.

With each stride, his left leg remains on the ground for 97 milliseconds, about 14 per cent longer than his right leg. (85 ms). This 13–14% variability is a considerable outlier; most elite sprinters stay within 0–7%.

You can see this at play in, for instance, the 2017 IAAF World Championships in London (here are the top 3 finishers): Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run

But I digress. Those years (2008–09) were exciting times, during which Usain seemed to get endlessly faster, and the sky was the limit; everyone was talking about him going sub-9.4. That never came to pass (boy, did I wait for it, though), but Usain is still undoubtedly the fastest sprinter who ever lived.

Usain rounding the bend is one of the more awe-inspiring things you’ll ever see in track and field.

The 200m final in Beijing. That gap, my gosh!

What is the fastest possible speed a member of the human species can achieve on flat ground, knowing our limitations?

The fastest human we know about was an Aboriginal youth, probably a boy, who left his footprints in Australia about 40,000 years ago. His changing stride indicates that he was accelerating and that at top speed, he was probably faster than Usain Bolt. I suspect he was chasing lunch.

It’s still Usain Bolt from Jamaica who holds the title of the fastest human being ever recorded in sprinting. He set the world record for the 100 meters with a time of 9.58 seconds and the world record for the 200 meters with a time of 19.19 seconds during the World Championships in Berlin, Germany, in August 2009.

Speed: Who is the fastest man on Earth?

No exact data is available, but I believe the Rarámuri people are probably the fastest ones on Earth, and they are known to man. They are a Native American people, a small tribe of northwestern Mexico known as Tarahumara. They are renowned for their long-distance running ability.

Rarámuri means “runners on foot” or “those who run fast” in their native tongue.

The Tarahumara are also known for their ability to run down deer and wild turkeys. Anthropologist Jonathan F. Cassel describes the Tarahumaras’ hunting abilities: “the Tarahumara literally run the birds to death. Forced into a rapid series of takeoffs, without sufficient rest periods between, the heavy-bodied bird does not have the strength to fly or run away from the Tarahumara hunter.”

These tribes can easily cover a distance of 300 km in just one go, displaying their superior health.

At what temperature does honey catch on fire?

Who was the fastest human being ever recorded and how much could they run